ISABELLE MCCORMICK

Who is Isabelle?

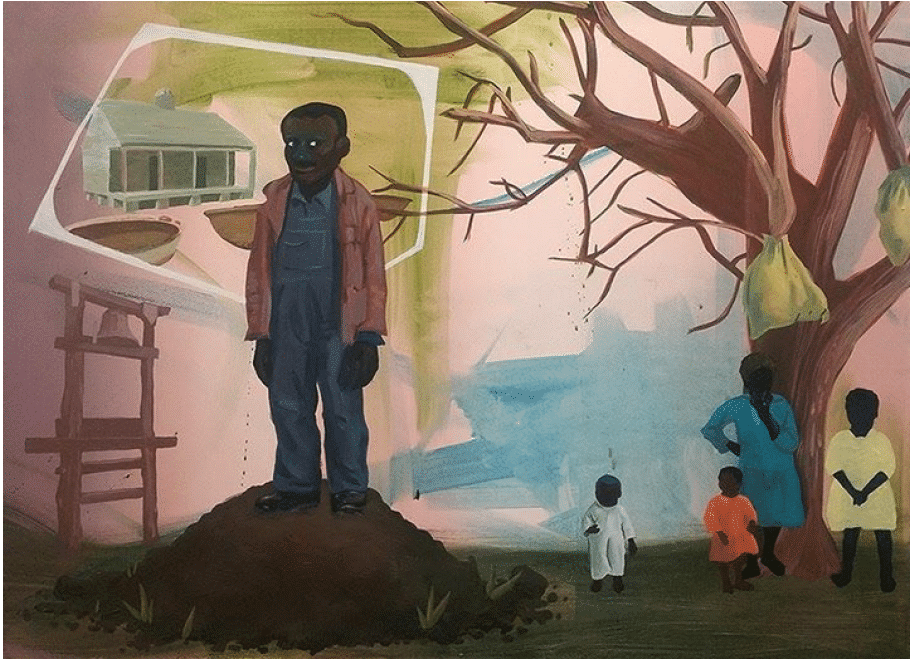

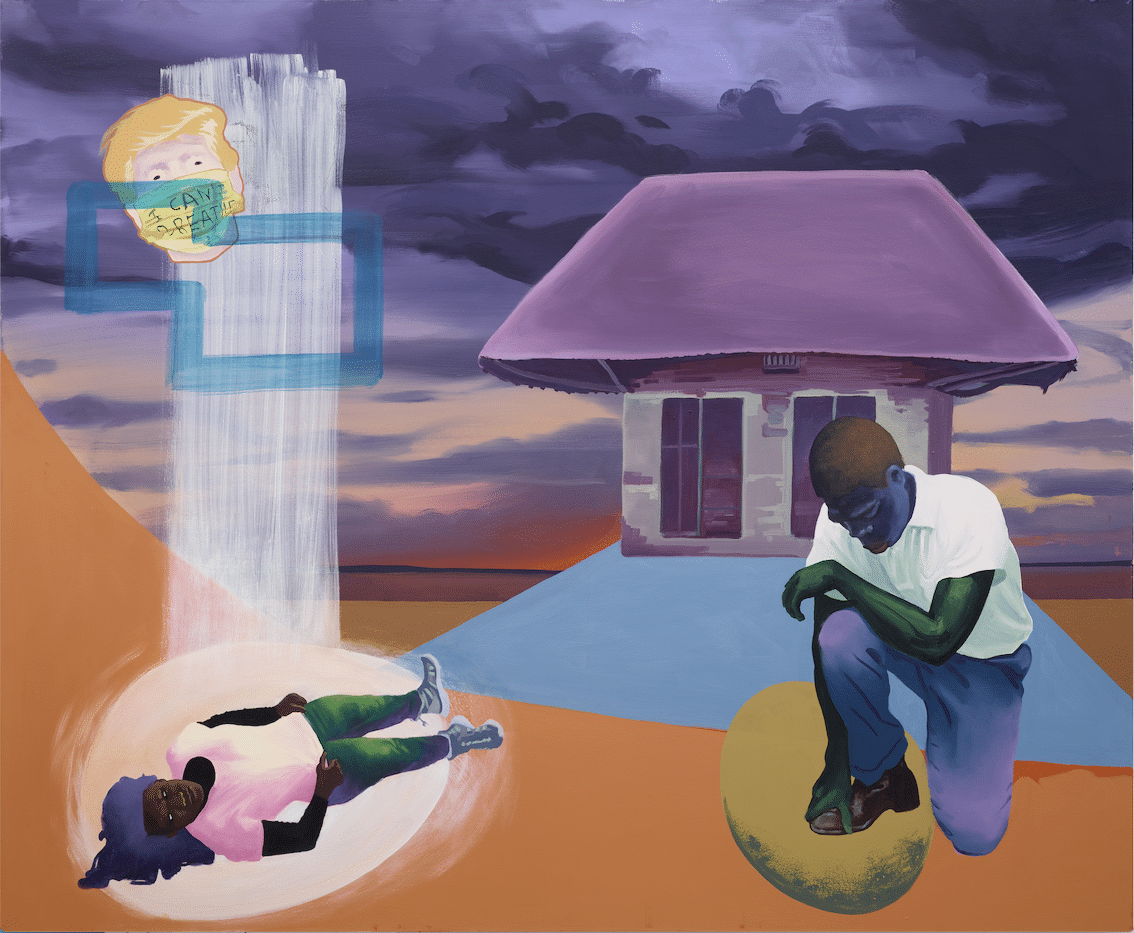

Isabelle McCormick (b. 1992) is a painter from St Paul, Minnesota, currently based in Detroit.

She received her MFA in Painting from Cranbrook Academy of Art in May 2021 and graduated from the Brown University | Rhode Island School of Design Dual Degree Program in 2015 with a BFA in Painting and BA in Literary Arts.

Isabelle’s work navigates the distance between the bodily self and social media façade, employing traditional oil painting techniques to render virtual space.

The artist spent two years in her mother’s native country Rome, Italy, serving as the Resident Fellow for the Rhode Island School of Design | European Honors Program. She has worked in Museum Education and Public Programs at the San Diego Museum of Art, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, Italy, and the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Isabelle has exhibited her work nationally in New York, Detroit, Providence, Minneapolis, and San Diego, as well as abroad in Italy, Greece, and Lebanon. Her second solo show will open summer 2022 in Detroit.

ARTIST STATEMENT

“I am struck by the centrality of the Venus figure throughout the complicated Western canon and its enduring influence across the social media screenscape. At the meeting of technology and art history, I examine the relationship between self-surveillance and feminine archetypes enmeshed in the Venus pudica tradition. I rethink the bathing goddess’s gestures and the anticipated voyeuristic gaze—represented in my work as the smartphone camera lens. There is a reverence for “techne” in my formal approach that redoubles this investment in history. I employ traditional oil painting techniques to render virtual space, and further unpack how Internet culture remodels the visual language of femininity. I draw from the Western tradition to at once learn from “the old Masters” while reclaiming narrative control over expressions of female sexuality. Living in a society where the pressures of la bella figurapervade, the battle over the female body has become the material meat of my work. In this vein, I look to Betty Thompkins, Ghada Amer, and Mickalene Thomas.

The classical idealization of the nude figure became a precondition for “great art” during the Renaissance. But without access to nude models, women artists were deprived of the opportunity to make major works of art. Painting my own body has become a radical stance in my practice to push back against this history. I challenge the rules of propriety, defined by Linda Nochlin as the historic double standard that allowed a “woman to reveal herself naked-as-an-object for a group of men,” but forbade women artists from participating in the same study (Nochlin 160). I am drawn to women’s self-portraiture as a way to wrestle with this history that banned women from art academies before the nineteenth century. Women’s self-portraiture is a genre in itself, “a way of understanding what it was—and is—to be a woman and an artist” (Borzello 7). From Artemisia Gentileschi to Frida Kahlo to Gina Beavers, I pull from this lineage to make sense of self-representation in the Digital Age.

With the expansion of the leaderless Internet and birth of the smartphone, women en masse have the tools to redefine the ideal feminine outside of art historical precedents. Still, I question whether modern technologies have ushered in an era of empowered self-expression, or reinforce timeworn patriarchal motifs. I am interested in how traditional notions of femininity are rebranded for online audiences and younger generations. I capitalize on the fluency of emoji culture to articulate these through lines: a cherry blossom emoji censors my nude selfies; the crying face Kimoji wails next to Botticelli’s Venus. Icons of Internet culture bump up against those of the art historical past to illustrate how we still operate under this default assumption: “it is politically important to designate everyone as beautiful, make sure everyone can become and feel increasingly beautiful” (Tolentino 80). (Enter self-care and wellness routines as beauty capital.) How might gender dynamics shift if beauty mattered less? My paintings ask how the selfie is shaped not only through the lens of technology but by the “hidden he” that encompasses Western visual culture (Nochlin 145).

I frame my creative approach as femme finish fetish, an alternative to the 1960s Los Angeles style that evoked the clean lines of commercial production. The LA Cool School’s surface obsession is symptomatic of a larger fixation on exteriority in Western culture. In the 21st century, social media has accelerated this trend. I cultivate a material sense that imitates self-branding, to channel the language of social media influencers and beauty bloggers. Gold leaf, metallic paint, and Swarovski crystal rhinestones gesture to Snapchat filters, where human flesh is made to sparkle. Smoothed out brushstrokes mimic the spot healing brush on Photoshop, used for rendering “poreless” skin. I contrast this hard-edged figuration with chunky, cakey texture. Using frosting piping techniques, I embrace the frivolity so often linked to the feminine domain. Plaster molds add three-dimensional depth, while complicating the flatness of my painting surface and its reference to the smartphone screen.

A hollow, standalone avatar emerges across my work. She is glued to the screen, her iPhone a phantom limb. She inhabits the pornographic imagination, which “tends to make one person interchangeable with another and all people interchangeable with things” (Sontag 219). My compositional framing heightens this objectification. Cropping from the neck down positions the viewer behind the eyes of my subject by way of Joan Semmel and Luchita Hurtado. It also references the cropping of nude selfies in sexting exchanges. The resulting figure is fragmented, much like the classical material informing my work: marble sculptures of Venus, damaged or “cropped” by the passage of time. She is broken but monumental, painted on a larger than life scale to challenge the notion that a woman’s body must be contained. Her ballooned body parts—plastic and malleable, seductively painted—adhere to a new canon of grotesque manipulation that traverses the physical and digital. I look to women artists critical of the pressure to put your best face forward, from Orlan’s performances of plastic surgery to Cindy Sherman’s Instagram page.

By curating a sense of identity online, we create distance between the bodily self and social media façade. Painting is a way for me to navigate this distance between the physical and virtual. Wading in this space between helps me better understand what it means to be a woman and artist in our hyperbolic world of retouching apps and reality TV. Growing up in the Information Age where selfhood has become aesthetic commodity, I turn to the tradition of women’s self-portraiture to digest digital zeitgeist through the handmade.”

Sources

Borzello, Frances. Seeing Ourselves: Women’s Self-Portraits. London: Thames & Hudson, 2016.

Freidan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. New York: Dell Publishing, 1983 (1963).

Grosz, Elizabeth. “Women, Chora, Dwelling.” In Space, Time and Perversion: Essays on the Politics of Bodies.

New York: Routledge, 1995.

Henrich, Joseph. The Secret of Our Success: How Culture is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species,

and Making Us Smarter. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16.3 (Autumn 1975): 6-18.

Nochlin, Linda. “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?.” In Women, Art and Power, 145-178. New

York: Harper & Row, 1988.

Russell, Legacy. Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto. London: Verso, 2020.

Sontag, Susan. “The Pornographic Imagination.” In A Susan Sontag Reader, 205-233. New York: Farrar, Straus and

Giroux, 1982.

Steyerl, Hito. “In Free Fall: A Thought Experiment on Vertical Perspective.” E-Flux, no. 24 (2011): 1-11.

https://www.e-flux.com/journal/24/67860/in-free-fall-a-thought-experiment-on-vertical-perspective/.

Storr, Will. Selfie: How We Became So Self-Obsessed and What It’s Doing to Us. New York: The Overlook Press,

2018.

Tolentino, Jia. Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion. New York: Random House, 2019.

Twenge, Jean M. and W. Keith Campbell. The Narcissism Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlement. New York:

Simon & Schuster, 2009.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. Richmond, Surrey: Alma Classics, 2019 (1929).

AUTHOR:

Août Gallery / Isabelle McCormick

Date:

November 24, 2021

Category:

PaintingsDate:

November 24, 2021